Remain II

An open question — one not squarely addressed in my last entry here, Remain in the Climate Treaty — is whether the President may unilaterally lawfully withdraw the United States from the world’s climate treaty.

The question is important because, as the International Court of Justice determined last year, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (“the Climate Convention,” “the Treaty,” or “UNFCCC”) is a key source of the legal obligation imposed on every nation to combat dangerous climate change.

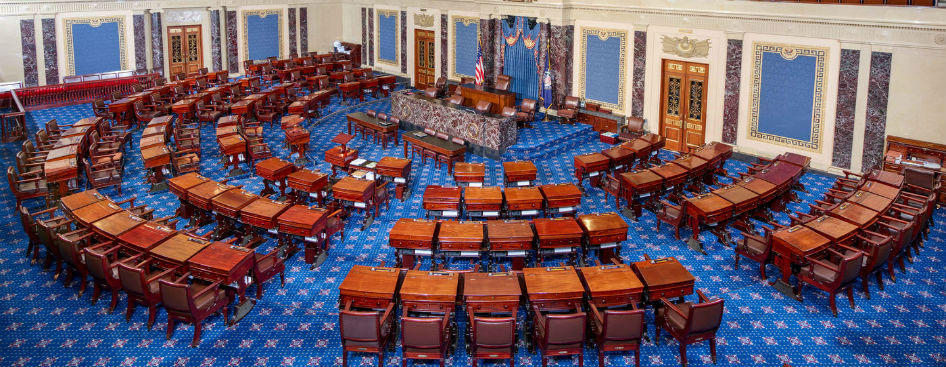

In brief review: on June 12, 1992, at the Rio Earth Summit, President George H. W. Bush signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change on behalf of the United States. But he was barred by the Constitution from formally entering the Treaty, on behalf of the nation, until the US Senate provided its advice and consent. Specifically, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution vests the President with authority to “make” treaties only “by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate [] provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.”

Pursuant to that Constitutional framework, President Bush submitted the Convention to the US Senate for its deliberation on September 8, 1992. One month later, on October 7, 1992, the Senate gave its concurrence in a unanimous “division vote.” Six days after that, October 13, 1992, President Bush signed “the instrument of ratification,” formally entering the nation into the Treaty. In his ratification signing statement, President Bush called the Climate Convention “the first step in crucial long-term international efforts to address climate change,” one that is “comprehensive in scope and action-oriented.”[1]

On first blush, it seems implausible that the President should be able to unilaterally withdraw from a treaty without some similar Senate vote of concurrence, as I noted in a recent discussion with the astute gang at the Climate Emergency Forum.

After all, along with the substantive provisions of the Constitution itself and other sources of federal law, the Constitution specifies that “all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” US Constitution, Article VI. Indeed, the President violates the law — and may be held to account by our federal courts — when he acts contrary to his duties prescribed by the Constitution (including the duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Article II, Section 3). Similarly, he may be held to account for violating any federal law. The President, who is, after all, not a King, cannot withdraw from these sources of law simply because he prefers not to abide by them. Instead, he is free to seek a change in then. Why, then, if he may not unilaterally withdraw from those sources of the supreme Law of the Land, should he be deemed cloaked in authority to unilaterally withdraw the nation from a treaty to which the US Senate had dully provided its advice and consent?

The President, who is, after all, not a King, cannot withdraw from these sources of law simply because he prefers not to abide by them.

The question is one that has never been resolved by our Supreme Court, though in 1979 it came close.

Effective on January 1 of that year, President Carter terminated diplomatic relations and withdrew the United States from its 1954 Mutual Defense Treaty with Taiwan, while newly recognizing “the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government of China.” Several Members of Congress, including Senator Goldwater, challenged the constitutionality of President Carter’s unilateral withdrawal from that Treaty. A federal district court then found for Goldwater et. al, determining that the President’s termination of the Treaty with Taiwan was ineffective because, among other reasons, the U.S Senate had not provided its consent to withdrawal.

President Carter then appealed, and the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the district court, holding that the President had sufficient authority to terminate the defense treaty with Taiwan because, among other things, “the determination of the conduct of the United States in regard to treaties is an instance of [] the “foreign affairs power” of the President.”

Goldwater then sought review of the D.C. Circuit decision, and in a plurality decision the Supreme Court held for President Carter.

In brief, a plurality of four Justices — Rehnquist, joined by Stewart, Stevens and Chief Justice Burger — wrote that the case needed to be dismissed because it presented a basic question that is “political” in nature. [The quote marks around the term political were those of the Court.] Their reasoning, alas, was circular and conclusory. The case, they said, was too “political” for decision because it involved “the authority of the President in the conduct of our country’s foreign relations and the extent to which the Senate or the Congress is authorized to negate the action of the President.”

Three Justices – Blackman, White, and Brennan – dissented. Justice (Brennan) dissented outright, emphasizing that he would have affirmed the appellate court’s determination, namely that the President was vested with clear authority to recognize “the Peking Government” and, as a “necessary incident” to that recognition, needed to abrogate the defense treaty with Taiwan. For their part, Justices Blackman and White would have “set the case for oral argument and give[n] it the plenary consideration it so obviously deserve[d].”

The most compelling substantive position, in my view, was advanced by Justice Powell. He concurred in the judgment that the case needed to be dismissed, but on a ground different from the plurality. In brief, Justice Powell wrote that the case was not too political for judicial determination. Rather, it simply was not ripe for decision.

Among other things, Justice Powell found it important that the Senate had not actually disapproved of President Carter’s withdrawal from the defense treaty. Indeed, the Senate had the opportunity to consider a resolution by Senator Byrd, namely one declaring “the sense of the Senate that approval of the United States Senate is required to terminate any mutual defense treaty between the United States and another nation.”

But the full Senate never voted on the Byrd resolution. And, indeed, neither did the House of Representatives in any direct way disapprove of President Carter’s unilateral treaty termination. Accordingly, Justice Powell wrote, “[i]f the Congress chooses not to confront the President, it is not our task to do so. I therefore concur in the dismissal of this case.”

All in all, the case Goldwater v Carter (1979) resolved absolutely nothing.

All in all, the case Goldwater v Carter resolved absolutely nothing. In retrospect, it provided little guidance to resolve the present problem of the President’s determined attempt to unilaterally from a universal treaty that without question advances the nation’s interest in combatting dangerous climate change.

However, Justice Powell’s concurring opinion at least provided a hint as to what might be done in our present circumstance. That is, if the Senate were really determined to preserve not only its Constitutional role but also the nation’s continued participation in the world’s climate treaty, then, at minimum, Senators could draft a resolution of disapproval and marshal it through to a final vote.

Under the Convention, any nation’s formal withdrawal takes 12 months to become effective. There is, then, only a little time to spare. U.S. Senators seeking to ensure that the nation remains in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, have got one year to get it done.

[1] George H. W. Bush, Statement on Signing the Instrument of Ratification for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, October 13, 1992.