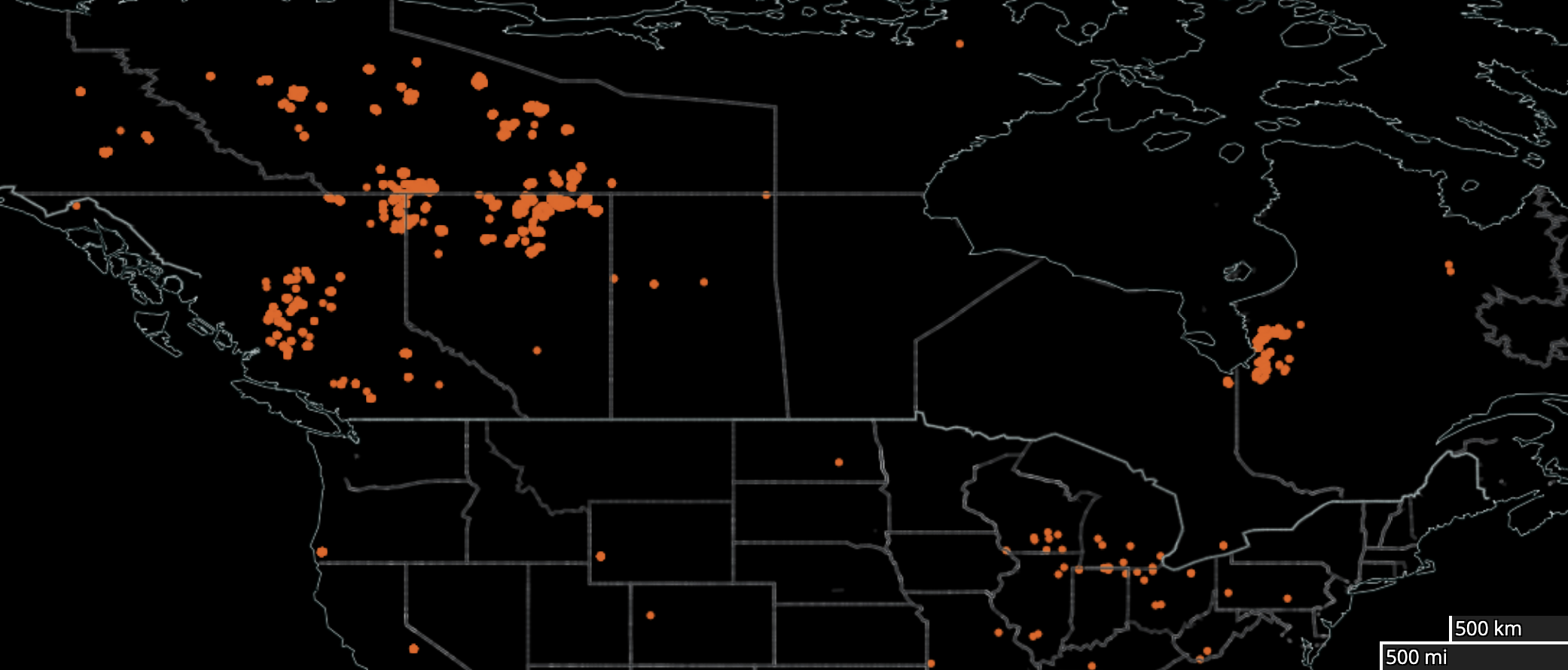

Wildland fires in Canada were tamped down a bit last week, particularly in north-central Quebec where a large low-pressure system was “wandering around the Hudson Bay area,” delivering some rain. Nonetheless, a great swath of Canada’s wildland remains on fire, particularly in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and even in Quebec.

We produced the arresting night image above with NASA’s Worldview mapping tool, aggregating hot spots exceeding 375m in diameter for the week ending July 23.

Nature and civilization are shaped by fire, of course, and vice versa. As NASA explains, in a nearly buried note:

Fires can be set naturally, such as by lightning, or by humans, whether intentionally or accidentally. Fire is often thought of as a menace and detriment to life, but in some ecosystems it is necessary to maintain the equilibrium. For example, some plants release seeds under high temperatures that can only be achieved by fire. Fires can also clear undergrowth and brush to help restore forests to good health. Humans use fire in slash and burn agriculture, to clear away last year’s crop stubble and provide nutrients for the soil and to clear areas for pasture.1Available here.

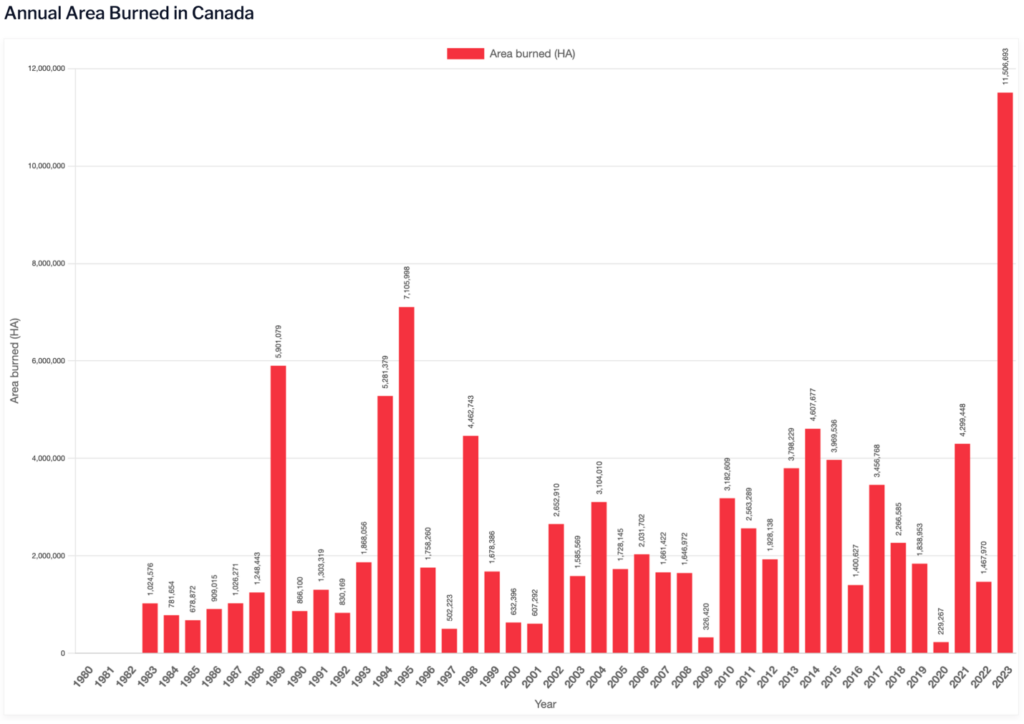

And yet, at this writing, the year-to-date wildfire extent in Canada already far exceeds any of its annual totals from 1983, according to data maintained by the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre. Fig. 1. The 11.5 million hectares burned is roughly 28 million acres and over 44,000 square miles — about the size of Pennsylvania. Canada still confronts 1052 active fires, of which 670 are deemed out of control.2Data from the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre for July 23, 2023. Some of these are extremely large. For instance, an uncontrolled wildland fire to the southeast of Sakima, Quebec spans 1.041 million hectares3 Accordingly to an Interactive map maintained by the Natural Resources Canada. — an area nearly the size of the state of Connecticut.

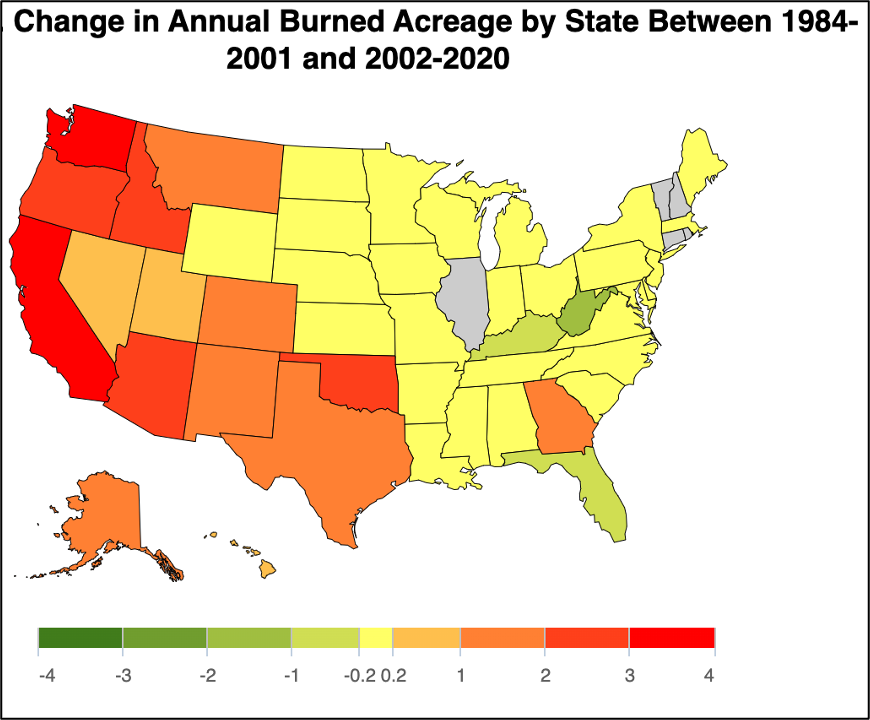

As for the lower 48 states, the year-to-date extent of wildland fire is a factor of 30 less than in Canada. But the pattern over time may be worse — particularly for the western US. As illustrated in a recent EPA-produced map, “the number of acres burned in each state as a proportion of that state’s total land area has changed over time, based on a simple comparison between the first half of the available years (1984–2001) and the second half (2002–2020).”

See Fig. 2.

Thus, the area burned per square mile has increased by 3.61 acres in California, 3.01 acres in Washington, 2.83 acres in Oregon, 2.57 in Oklahoma, 2.28 in Arizona, and 2.21 in Idaho. [There are 640 acres per square mile.]

Depending on its location and the wind, an out-of-control wildfire can turn deadly quickly. Witness the Marshall Fire, whipped by 90+ mph westerly winds, that tore through Boulder, Colorado on Dec. 20, 2021. Or the Lytton Creek Fire of June 30, 2021, that burned through Lytton, BC a day after that town’s recording of the highest temperature ever in Canada — at 49.6 °C (121.3 °F). Or the Holiday Farm Fire, a conflagration fanned in part by an unusual easterly wind that scorched communities up the McKenzie River Valley to the east of Springfield, Oregon in September 2020. Or the deadly Camp Fire that torched the town of Paradise, California in November 2018, killing at least 85. Or the massive Rim Fire of 2013, that burned 402 square miles on Yosemite’s western border, the largest wildfire in Sierra Nevada recorded history.

No end in sight during these dog days of summer.

Most of the recent large burns, and perhaps all, were fueled by drought and heat conditions rendered more severe by human-caused global warming — “the main driver of the increase in fire weather in the western United States,” according to NOAA. Indeed, a PNAS-published study focused on area burned by California wildfire finds that “nearly all the observed increase in [burned area] is due to anthropogenic climate change.”

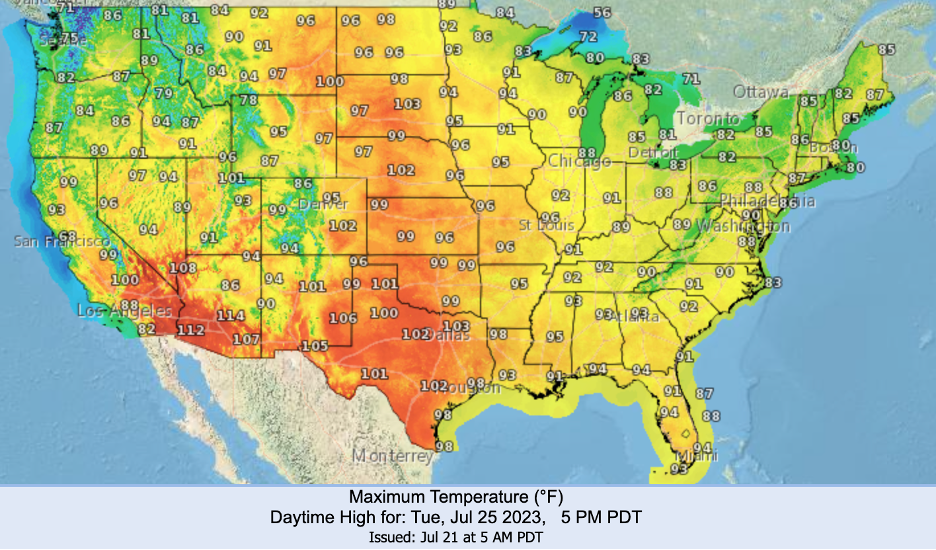

At present, there is no end in sight as one after another heat wave threatens to press through, and perhaps beyond, these dog days of summer. In Fig. 3, below, we show NOAA’s forecast for Tuesday, July 25, 2023. Temperatures nearing 100oF, or higher, are anticipated for California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Montana, Wyoming, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota.

Nearly a third of residents in western states live in areas deemed at significant risk of wildfire, according to a 2022 Washington Post study of relevant data, with nearly 45 percent at significant risk in mountain states (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming) and 27 percent in the pacific coastal states (Washington, Oregon and California). The share of residents at significant risk of wildfire in west south-central states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas) is also quite high, at 27.2 percent. With continued high fossil fuel emissions to 2052, the share of residents at significant wildfire risk is expected to climb substantially — to nearly 40 percent in west and south central states. The Post study also reveals that Native American and Hispanic communities are disproportionately hard hit by wildfire.

Where there is wildland fire, of course, there will be smoke, and for all practical purposes it cannot be contained. Already this summer, and on multiple occasions, people across the Midwest and along the Eastern Seaboard have received a “horrifying taste of the brutal cost of climate change more often borne by others elsewhere.”

Where there is wildfire there will be smoke, and it cannot be contained.

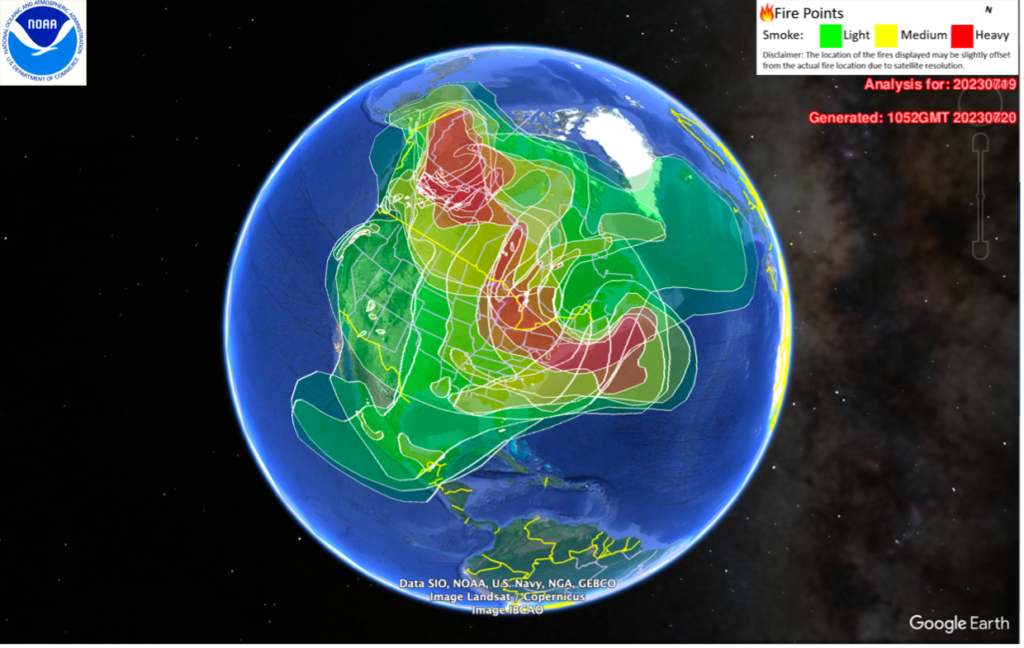

With Fig. 3, below, we show a NOAA-generated map of Canada-only fire and ensuing smoke plumes. That wildfire smoke has recurrently blanketed and degraded air quality in Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa, and in points south including Chicago, Pittsburgh, New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington DC. Indeed, for a time in late June, Toronto’s air quality was the worst in the world.4Dan Bilefsky, The air quality in Toronto is among the world’s worst, in Wildfire Smoke: Smoke From Canada Fires Stretches From Midwest to East Coast, NY Times, June 29, 2023.

NASA satellites revealed that by late June Canadian wildland fire smoke reached to southwestern Europe. However, the ensuing air quality degradation in Europe was minimal “compared to unhealthy and hazardous air quality in the smoke-affected parts of Canada and the United States . . . because most of the smoke that reached Europe was higher in the atmosphere, where it is less likely to affect human health.”

Authorities even needed to close the Acropolis in Athens.

Over the last few weeks, Europe’s own heat waves have spawned wildland fire and noxious smoke of their own. Last week in Italy, for instance, extreme heat red alerts were issued for 23 cities, “indicating that the heat is so intense it poses a risk to the entire population,” while in Greece, “in the face of the ongoing heatwave and the potential strengthening of winds,” the Culture Ministry “closed all archaeological sites and monuments, including the Acropolis in Athens, each afternoon through to Sunday.”

The Biden Administration has proven itself willing to reverse some of the more egregious policies of the Trump crew — not only on the environment but also with respect to democracy, human rights, health care, and income support for vulnerable sectors. But the Biden team’s efforts on climate have been meek at best, and too little even to secure the president’s own public commitments.

Additional fossil fuel burned anywhere exacerbates the crisis everywhere.

Nowhere is this more clear than the still uncontrolled production of fossil fuels in the US. Not only has Biden outpaced Trump in approving oil and gas drilling on public lands, but the Biden team’s notable Clean Air Act initiatives — issuance of draft rules to reduce GHG emissions from vehicles and power plants over the next few decades — may further induce the industry, paradoxically enough, to increase its exports of oil and gas to the international market. Indeed, since 2020 the US has been a net exporter of oil. And an additional barrel of oil consumed anywhere in Mexico, Canada, China, The Netherlands, or South Korea — to name the five top recipients of US petroleum exports — only serves to exacerbate the climate crisis confronting the United States as much as if that fuel were burned in Richmond, California, for instance.

Recently, the US EPA reanalyzed the social cost of greenhouse gases, to reflect “advances in the scientific literature on climate change and its economic impacts.” Such calculations enable one to estimate, in dollars, the damage to society from each additional tonne of GHG emissions. Alternatively, the figures can be used to estimate “the net social benefits of reducing [such] emissions.” In constant US dollars, the Agency determined the social cost of CO2 to $190 per tonne, rising to $410 by 2040. Similarly with respect to methane pollution (CH4), the Agency found $1,600 in damages for each additional tonne of CH4 emissions in 2020, rising to $6,800 by 2040.

The number, indeed, is larger than the budget deficit.

Considering that US emissions totaled an estimated 6.340 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalents in 2021, the social cost of that one-year of pollution was at least $1.2 trillion. That is real money, larger indeed than our currently projected federal budget deficit. The social cost will rise to $2.6 trillion by 2040, unless we change course. And yet, our chief environmental agency has imposed no limit on fossil fuel production. Neither has it imposed a rising carbon fee geared toward limiting such production.

Our shamefully “insufficient” effort must not stand. Indeed, the federal government’s continued dalliance in the face of record global temperatures, wildfire, and other climate impacts is virtually inexplicable unless, as the climate scientist James Hansen recently suggested, albeit with considerable understatement, we have become “damned fools.”

On the presumption that we wish to wise up fast, what more might the US do to arrest the climate crisis? We will have occasion to return to that relevant question in this space soon enough.

Footnotes:

- 1Available here.

- 2Data from the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre for July 23, 2023.

- 3Accordingly to an Interactive map maintained by the Natural Resources Canada.

- 4Dan Bilefsky, The air quality in Toronto is among the world’s worst, in Wildfire Smoke: Smoke From Canada Fires Stretches From Midwest to East Coast, NY Times, June 29, 2023.